I’ve been thinking about travel writing lately, but this is not a travel piece. This is a train wreck.

I initially came to Baltimore to explore the medical archives at Johns Hopkins Hospital—the very place where John Money, father of ‘gender identity,’ put his ideas on gender into practice upon the minds and bodies of intersex children and transgender adults.

I came to look at the papers of Dr. Milton Edgerton, one of the lead characters in my book-in-progress on the history of transgender medicine in the United States. But I ended up spending most of my time looking through Money’s papers.

John Money was a meticulous (and egotistical) archivist of his professional life. He left behind documents that definitively prove that anti-trans doctors and administrators at Johns Hopkins purposefully created junk science for the purposes of legitimating the closure of their Gender Identity Clinic in 1979, an act that precipitated the closure of most mainstream transgender medical clinics in the U.S. in the 1980s. In Hopkins’ campaign of transphobic pseudoscience, I see so much of our current moment, with our federal government just last week, while I was in Baltimore, releasing a major junk-science report condemning transgender medicine.

Intersex rights activists frequently (and appropriately) look back at Money as a monster. And the ways he willy-nilly assigned (and reassigned) sex to intersex children was monstrous. But I also saw so much of myself in his papers: in his dogged post-1979 efforts to defend transgender healthcare as a legitimate field of medicine while the rest of the medical world shimmied away from him on that point (a shift in practice that would last for over a generation, until trans medicine went mainstream again in the 2010s).

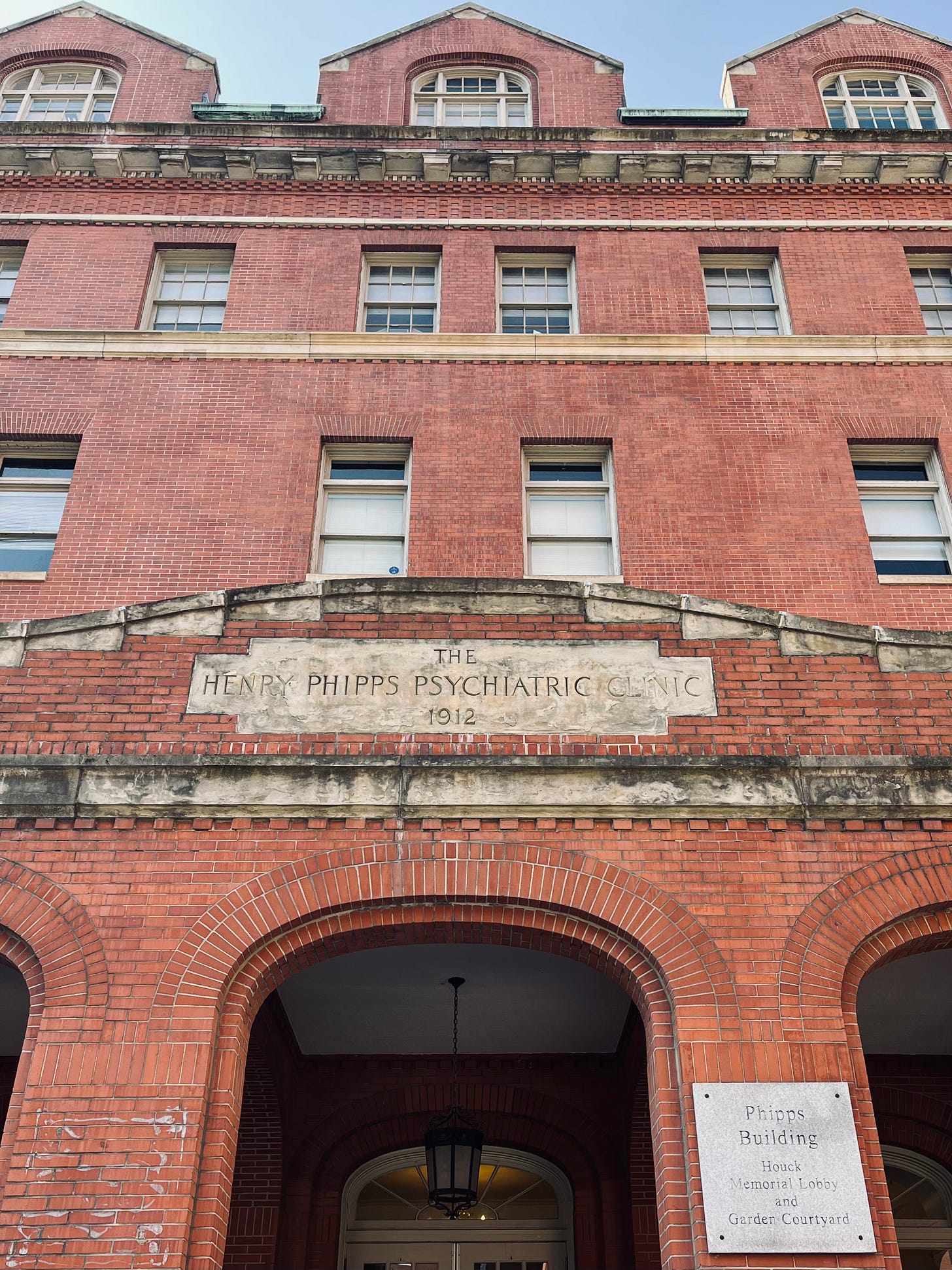

After I finished up in the archives, I went poking around the Johns Hopkins Hospital complex—six square blocks in the heart of East Baltimore where intersex and trans patients’ lives were changed, for better, and for worse, and the world’s leading scientists studied their bodies, developing theories about sex and gender that still haunt us to this day.

I saw the building where John Money long had his fourth-floor office. (And three stories down, on the first floor, was the office of Jon Meyer, that skillful purveyor of anti-trans pseudoscience in 1979, who waited until Money was out of town on a summer trip back to New Zealand before he held a press conference on the ‘failures’ of trans medicine in the building next door.)

And I saw the building entrance where the very first transgender patient presumably walked in and was seen by the official above-board Gender Identity Clinic when it opened in 1966. She was a trans woman from New York City (presumably a patient of Harry Benjamin’s, who was referring patients via Money to the team at Hopkins).

I felt fairly fucked up by the Johns Hopkins Medical Archives. I saw that we are just in a continuous loop of pain: of patients seeking treatment, of scientists and clinicians studying us, of doors opening to us and then shutting in our faces. And I left Hopkins feeling very clear-eyed that we are heading into yet-darker days ahead for trans people’s bodily autonomy in the U.S., and around the world.

But my work was not done.

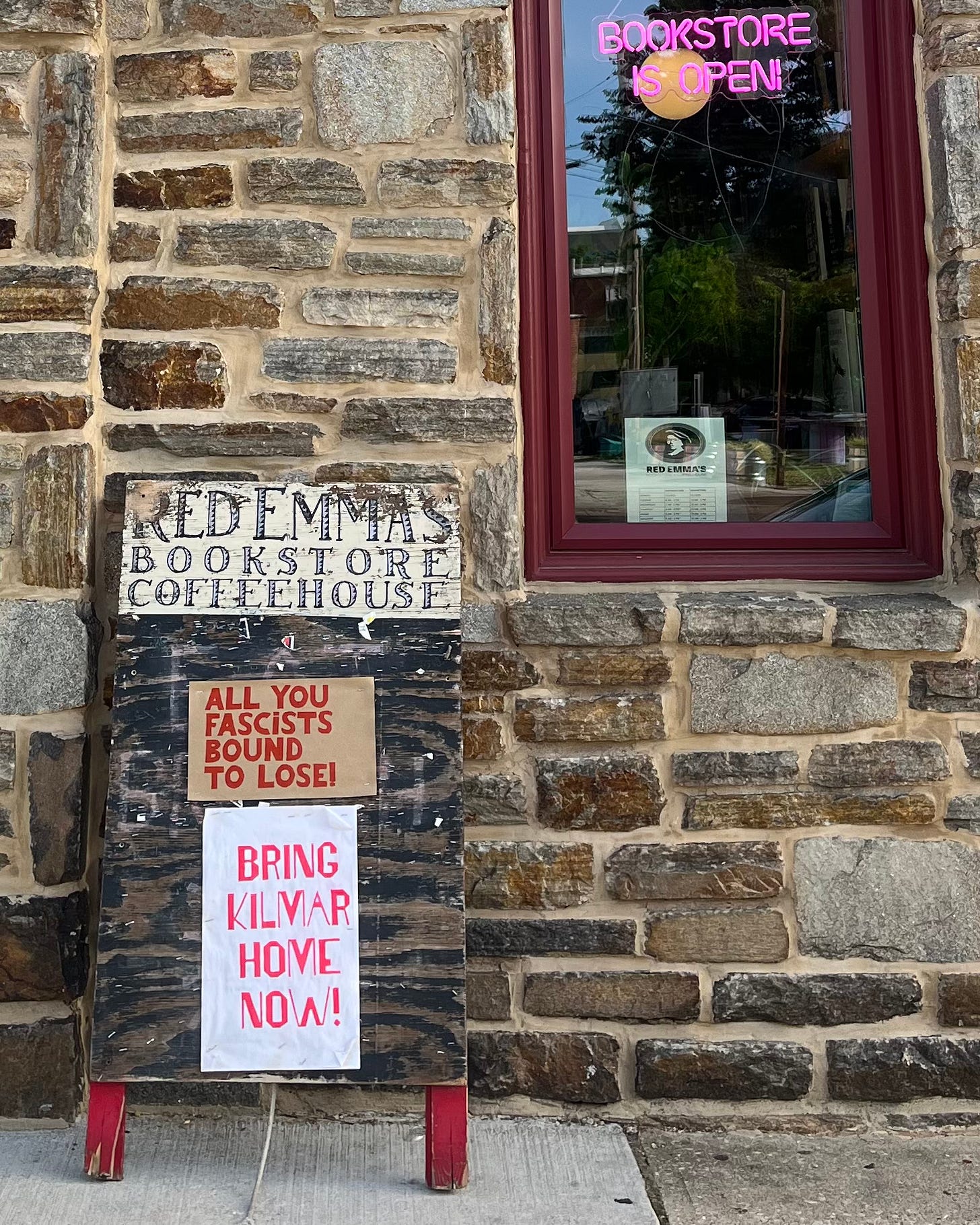

Consoling myself over a sloppy vegan Philly cheesesteak at Red Emma’s, Baltimore’s beloved anarchist cafe and bookstore, I discovered that Sarah Schulman was on her way to come speak in this very same anarchist bookstore about an hour later. So I stuck around. And to my surprise, Sarah approached me and asked me who I was. So we got to talking. I unloaded about Johns Hopkins and my research. What I really needed was to talk to my therapist, but of course one of the most-revered authors in my world would do. Our conversation shifted to Jewish activism, to anti-Zionist organizing. I told Sarah the truth of my wounded, conflicted, anxious heart, which is that I am afraid to speak out. I am afraid to be visible. I am afraid to put my neck out, because I am tired of being targeted by right-wing activists, because I am afraid of being sent to El Salvador. I am sick of being called brave. I would rather just be alive.

She listened graciously and empathetically, and acknowledged my decision to retreat from the front lines of academia. And yet, she told me, she was not timid. She was not going to shut up. In her talk later that evening, on her new book The Fantasy and Necessity of Solidarity, she said that in these dangerous times you must “think about what you can do, not what you can lose.” Because we are all going to lose things, she said: rights, money, maybe our jobs, maybe our lives.

And so then the next day I fueled up on delicious Jew food at Attman’s Delicattesen in Baltimore’s historic Jewish quarter—I ordered a mile-high lox and cream cheese bagel topped with lettuce, onions, and tomatoes, with a side of potato latkes with sour cream and applesauce—and then headed downtown to the National Membership Meeting of Jewish Voice for Peace, the largest Jewish anti-Zionist organization in the world, of which I am a member. (And this National Membership Meeting was the largest gathering of Jewish anti-Zionists in American history!)

Channeling Schulman’s courage, I swallowed my fear and joined in.

I marched. I chanted. I spoke out for a free Palestine.

I heard incredible speeches from a wide range of activists and speakers. Naomi Klein, Angela Davis, Raquel Willis. When Congressional Representative Rashida Tlaib spoke to us on the first night and told us stories of her Palestinian immigrant mother’s fears regarding speaking out, her counsel that it is better to keep your head down and not make a scene, but that Tlaib has always felt compelled to be loud, to be angry, to stand up in the face of injustices, I broke down sobbing.

I am writing this not-travel-writing essay on the train ride home. I feel so conflicted in my body. My stomach is churning in the trans and intersex past inside the Gender Identity Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital. My heart is reaching for the anti-Zionist future in which Jews do not commit genocide against others on the false premise of protecting Jews from pain. (Life is painful. We Jews know this. We of all people should never wish such pain upon others.)

Most of all, I feel afraid. I do. I can’t shed the premonition lurking over my shoulder foretelling my own persecution, my own suffering. But I keep thinking of Schulman’s advice. We are all going to suffer. Things are going to get worse. The question is: what are we going to do about it.

I loved this—Thank you for your vulnerability and openness about your process. I can’t wait to read more about your research!

thank you for this!