Death is Real

An excerpt from an essay on death, historical time, and the music of Phil Elverum

I’ve been up since 3:30am today. There was a chipmunk in my bedroom. (My childhood bedroom; I’m visiting home.) As my mother and I were chasing it around the house at 4am, we discovered a second one just watching us, like a kid plopped in front of a television set watching “Tom & Jerry.” Or, like Jerry watching Tom & Jerry. I couldn’t fall back asleep. The chipmunk infestation triggered my OCD. I took out my OCD workbook. (Thank God I brought it.) The prompt asked me to write out some of my current obsessions. I wrote down thirteen; five of them were related to houses: infestations, deterioration, fires, trees crashing through roofs.

After working in my OCD book for half an hour, I took a shower. In the shower, I was reminded of the first “mental health” essay I wrote after all this began. (By “all this” I am referring to this prolonged period of mid-life crisis / mental health crisis that I have been enduring for the past two and a half years since I turned 40 years old in the winter of 2022-2023.)

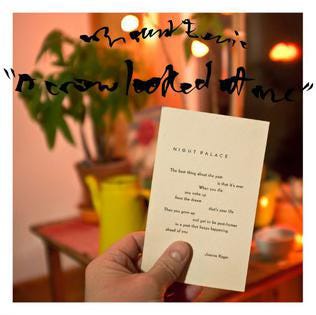

That essay is titled “Death is Real,” after a song by Mount Eerie. I wrote it in the fall of 2023 when an existential crisis—particularly regarding my mortality, precipitated by a scheduled surgery—was at its peak. I bought tons of books that season about existential psychology, especially books on death. And then I wrote thousands of words about it. I have never found a publisher for this essay, but I still hold it dear, as it captured a really awful moment for me and made something beautiful and memorable out of it.

Excerpt from my essay “Death is Real” (838 words)

There is a scene at the beginning of the film Annie Hall in which Woody Allen’s character Alvy Singer, seen as a child, is sitting in a mid-twentieth-century psychiatrist’s office with his mother. Young Alvy tells the doctor, “The universe is expanding. Well, the universe is everything, and if it’s expanding, some day it will break apart and that will be the end of everything.” To which his Jewish mother (sounding much like my own) snaps back, “What is that your business?!”

I imagine geologists and astronomers make peace with death. They think about big time, slow time, time like honey in a jar, sky-high mountains eroded into Appalachian foothills, stars whose lights dim forming space-time wormholes and galactic explosions. If you look at the sky on a clear night in Grayson County, Virginia, or wake to see the land brushed by the dawn wind, you can see these things happening over millions of years right before your eyes.

Historians, on the other hand, we struggle with death.

The singer-songwriter Phil Elverum, recording under the moniker Mount Eerie, writes music like a historian. In his devastating album A Crow Looked at Me, written and recorded in the weeks and months following his wife’s death from cancer, Elverum returns to the exact dates and scenes of her final days, and his first few weeks of unrelenting grief. Popular music doesn’t often include lyrics such as “In October 2015 I was out in the yard. I’d just finished splitting up the scrap 2x4s into kindling,” or “It’s August 12th, 2016. You’ve been dead for one month and three days.” These are lines like entries in a diary: an archive of life’s passing and the minutiae of one man’s suffering.

A few years later, on the album Lost Widsom Pt. 2, Elverum sings of visiting a museum, hoping that such an institution might bring at least “brief flashes of momentary clarity” to his agony. Yet, in the song “When I Walk out of the Museum” we witness him struggling with the “weight of all these other peoples’ ideas.” Rather than bringing clarity, the museum visit leaves him with “centuries of dust behind my eyes.” And outside the building, he confronts an “emptiness that cuts through… like a bowl beneath the sky, empty, not yet pregnant, fertile, without form.”

“It terrifies me,” he continues, “the raw possibility. I want to go back inside.”

The museum is full of dead things, dead people’s things. But out here, in the real world, we live on. Until we die.

I first experienced my own death in the summer of 2015. I was thirty-two. I was renting a room in Cambridge, not two miles from the gates of Harvard University where I was then on a prestigious fellowship conducting research at the Houghton Library. One afternoon, I was lying in a second-floor bathtub, staring out a small window several feet above my toenails. My eyes examined the muddled sky. Then, I suddenly felt my heart sink into my chest like an imploding star. My stomach dropped into my intestines. My breath choked. I felt a carving out of my insides, like an internal black hole. I immediately unplugged the bathtub drain, fearing I would drown. Over the next several hours I paced around Cambridge in my t-shirt and ripped jeans, frantically, chasing waning light, a cellphone pressed to my ear, talking to a lover, telling her “please just let me stay on the phone with you.”

Historians aren’t supposed to have a paralyzing fear of death during their prestigious fellowship at an Ivy League university, so I went back to the archives the next day and kept working, reading scribbled ink from the hands of people who had long ago perished. We are the merchants of death: rifling through the belongings of dead people who we don’t even know and we have no relationship to them and then transforming their lives into books and talks for profit. Maybe this is why I became an oral historian. Maybe I wanted to know more about how to live, and less about death.

When I walk out of the archives, much like Elverum stepping out of the museum, I am confronted by the terror of everything “rippling and alive,” which means someday it won’t be. Alvy was right: historians think we can preserve the story of humanity, but what happens when the sun swallows us whole? Who will remember us then?

I am fascinated by acid-free boxes. I recently ordered a huge stack of them, at considerable cost, that now sit in my bedroom filled with diaries and decades of personal correspondence. At forty I am too young to be preparing my archives, my will. I want to believe these things will outlive me, in some way continue me. Yet, in the hottest year on record on Earth while a defense contractor on the outskirts of my city is producing weapons that will be used in Gaza, I am certain acid won’t be the reason we are all forgotten.

A final word…

As I announced earlier this year, I am now offering personalized writing feedback & individual mentorship to other writers through 700/14! I call it the 700/14 masterclass. Signing up is simple. Click on the big purple button and become a paid subscriber to 700/14—for as little as $5 a month; the cost of a coffee once a month at your favorite coffee shop—and you’re automatically enrolled. You’ll get feedback on your own writing six times per year, and at the foundational membership level, you’ll also get biannual one-on-one mentorship calls with me.

Keep writing. Your voice is needed in this turbulent world. Sign up by clicking the purple button below.